After WorldBoston President Mary Yntema welcomed the capacity crowd to the October installment of Chat & Chowder, the speakers got right to work.

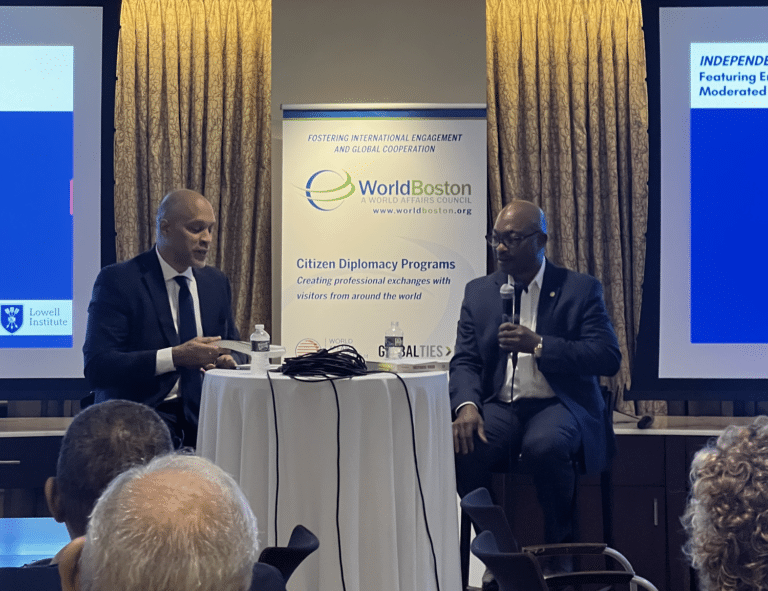

“Why did you write this book?” moderator Scott Taylor, the Dean of B.U. 's Pardee School, asked Harvard’s professor Emmanuel Akyeampong, as they settled into the beginning of what proved a brilliant and intellectually stimulating discussion. There were three reasons on his mind, Professor Akyeampong explained, when he set out to write Independent Africa: The First Generation of Nation Builders. First was to address questions about the relevance of the Decades of Independence in Africa. Second was to return us to the time in Africa’s history when the nationalists were at the forefront of political and economic thoughts and imaginations for their continent. Third was to make a book of major importance that would be accessible to both academics and ordinary people. He chose four men and their countries who offered vital insights into the history and analysis he sought to write: Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Ahmed Sekou Touré of Guinea, Léopold Sédar Senghor of Senegal, and Julius Kambarage Nyerere of Tanzania.

The conversation was well-centered, inviting us to reflect on the changes in and trajectory of Africa since the era of political independence. One might look at Africa today and wonder if independence really was worth the fight. More so, Akyeampong said, many scholars who look at African economic policies and developments often begin from the 1980s, the era now described as “the lost decade of Africa”. This was the decade in which the greatest economic crises broke out in African countries, and when the IMF and World Bank came in with the Structural Adjustment Programmes, economic policies, and models they hoped would rescue Africa. In this sort of narrative or analysis, the World Bank and the IMF appear as the main actors in Africa’s economic development.

In thoughtful conversation, however, Akyeampong and Taylor explained the necessity of returning to earlier decades, when the prospects were bright and the nationalists were at the crossroads of shaping the futures of their nations. It is right in that moment of history that we would better understand the meaning of African Independence, why it was sought and fought for, and the point at which African nations missed the mark. It is also in going back that we would better understand the essence of African nationalists, their collective and individual pre-Independence efforts and ideas, and the diverging and converging paths they took towards nation-building and economic development in their countries.

Questions and discussion points flowing through the room covered a wide range of topics: comparisons between the development paths of Africa and Asia; worries over high levels of indebtedness; China’s presence in Africa and its implications in the long run; African relations with Russia and the West; the meaning of true integration in Africa regionally and in the individual countries; the criticalness of making policies that center the region and emphasize technological transfer and infrastructural development; how much progress has been made in the fight against disease; and the place of post-war geopolitics in Africa.

Akyeampong and Taylor offered thoughts and answers, each from his own disciplinary background and both with great thoughtfulness. If one thing was true, it was that each person in the room cared about Africa’s past and future and sought to learn about the meaning of African Independence and prospects for a better and more stable Africa.

After the speaking presentation, lively informal conversation continued while many attendees purchased books, which Professor Akyeampong signed. On mine, he wrote, “To Ifeosa, for our shared vision of a prosperous and well-governed Africa.”

As we left through the lobby of the colossal Prudential Center that evening, attendee Rosaline Salifu of Harvard’s Center for African Studies said, “Professor, this conversation we just had there is so important. We must do this at Harvard. People really want to hear these things, and have discussions about how far we have come and where we are now as a continent.” Akyeampong smiled. Nothing was truer.