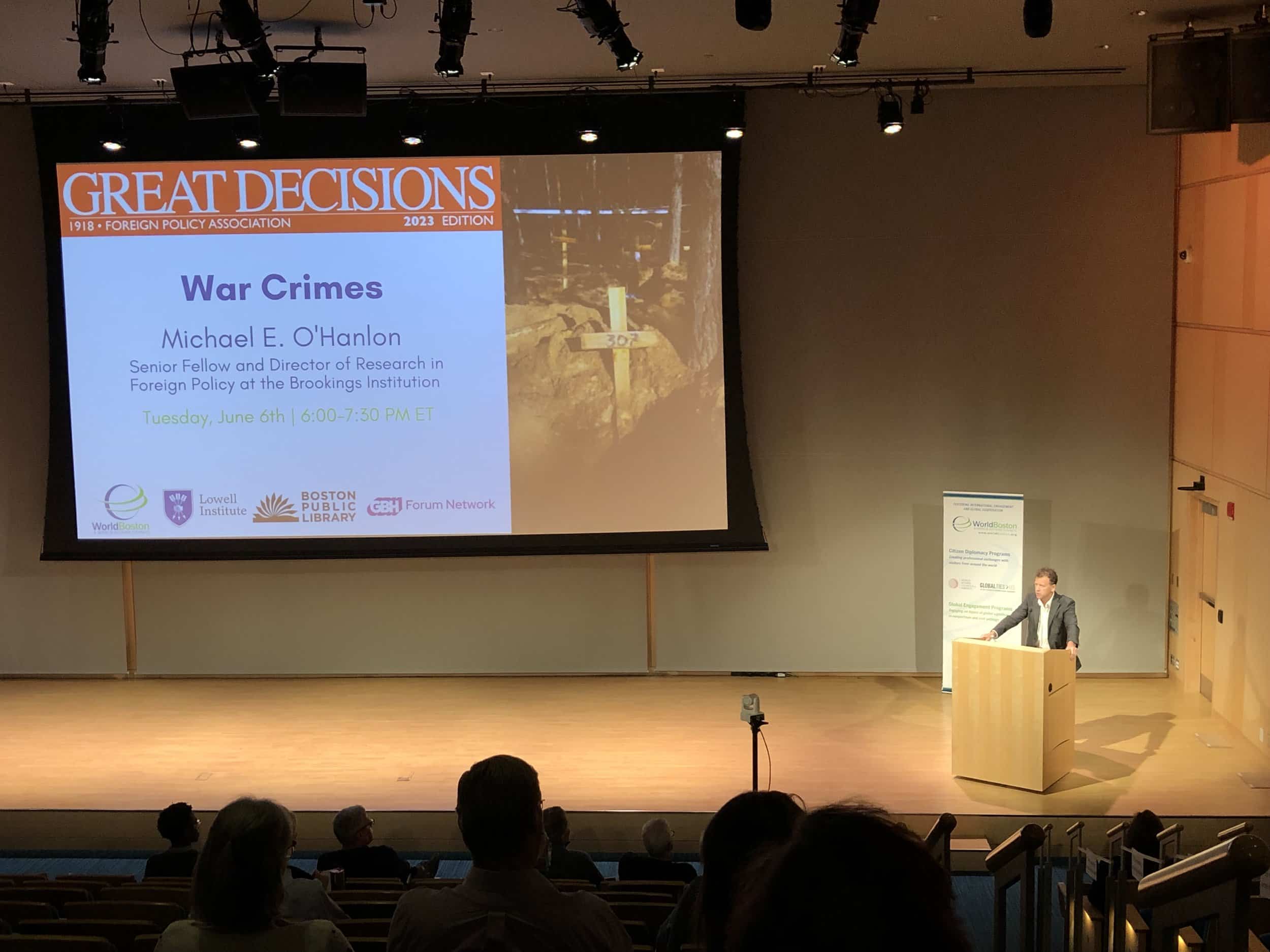

“Come on down, don’t be shy,” said WorldBoston President Mary Yntema, as she welcomed attendees into Rabb Hall at the Boston Public Library. On June 6th, 2023, WorldBoston hosted its penultimate Global Engagement program of the season on the pertinent topic of war crimes. Mary opened the talk with a framing of the one of the dilemmas of the topic, “You say invasion, I say liberation, and there we are,” and then introduced the speaker, Dr. Michael O'Hanlon. O'Hanlon is a Senior Fellow and Director of Research in Foreign Policy at the Brookings Institution, and his expertise in the field of national security and defense strategy added tremendous value to his lecture and the discussion that followed.

O'Hanlon outlined the two main questions he sought to address: (1) What exactly are war crimes? and (2) How will the war crimes committed in Ukraine be dealt with?

I'll pause here for a recap within my recap: In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea, a region that was internationally recognized as part of Ukraine, without the consent of the Ukrainian government, beginning the nearly decade-long conflict. A clear example of aggression, this act was widely condemned by the international community as a violation of Ukraine's territorial integrity and sovereignty. Russia then went on to support separatist groups (aka “pro-Russian rebels”) in eastern Ukraine by supplying them with weapons, troops, and funding, which escalated the conflict and contributed to — Can you guess what? You’re right — even more aggression. With the West’s support for Ukraine, Putin viewed the conflict as an attempt by the rest of the world to weaken him and those around him. Given NATO’s previous eastward expansion, he felt that the West was pulling Ukraine into its sphere.

O’Hanlon suggested bifurcating how we think about war crimes in Ukraine. First, there are “the full range of atrocities that have occurred under the guise of Putin’s special military operations, but clearly an aggressive war […] Then there are the questions of technical, provable violations,'' which are not to be confused with potentially immoral actions. O’Hanlon traced the evolution of how the international community has defined a war crime, from the Nuremberg Trials after the Second World War through the conviction of former Liberian President Charles Taylor in 2012.

As O’Hanlon reported that at the time of his talk, more than fifty thousand Ukrainian civilians have died, twelve to fourteen million have been displaced, and thirty thousand have died in combat, in addition to other fatalities. The prosecutor's general office has probably seen upward of one hundred thousand atrocities reported. However, the International Criminal Court did not believe that any of those atrocities could hold up in court. Though the ICC indicted Putin on the charges of deportation of children from Russian-occupied Ukraine in March 2023 , it’s important to note he was not arrested; he remains undeterred by the charges, and appears convinced he has done no wrong.

O’Hanlon has spent the last few years trying to understand Putin, who believes the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century was the dissolution of the Soviet Union; who thought the U.S. would link arms with Russia after he was the first leader to call President Bush after 9/11; and who most recently destroyed the Nova Kakhovka dam, cutting off the water supply for both Ukranians and Russians in Crimea for many years to come.

O'Hanlon invited the audience to see the world through Putin's eyes. “Imagine how Putin would rebut this allegation that we make in the West that Putin is a war criminal,” he began. O’Hanlon contends that Putin believes his own claims. In fact, Putin wholeheartedly believes that if the Russia doesn’t impose itself on Ukraine, then powers in the West could dismantle his empire. As O’Hanlon explains, Putin considers his actions to be creating “the great buffer”.

While condemning the atrocities in Ukraine, O’Hanlon asked audience members to examine Putin’s perspective and counterarguments he would make. In fact, under the same definition of war crimes, the United States might be considered guilty in several cases. Using the Vietnam war as an example, O’Hanlon stated: “Sometimes you make bad intellectual decisions in the midst of war about how to be tactical, especially in Vietnam. We had a military purpose, but the effect was to kill a lot of the Vietnamese.” Putin could also argue that the United States’ decision not to intervene in the Syrian Civil War only served to prolong the violence. Putin believes it is better to use the iron first to end conflict as quickly as possible, meaning, “Anything that could help end the war faster becomes justifiable.”

O’Hanlon concluded his remarks with a discussion of what the future may hold for Russia, Ukraine, and the rest of the world. He dismissed Ukraine's 10 Point Peace Plan proposed by President Volodymyr Zelenskyy as a non-starter, but he emphasized the resilience of the Ukrainian people and the need to persist in our efforts against Russia. By continuing to challenge Putin, the whole world telegraphs, “We are watching you, Putin,” limits his global support, and potentially holds him accountable in an international tribunal. However, O’Hanlon warns we must be realistic about potential terms of a peace deal and be very specific in detailing war crimes in order to strategically address them.

Mary invited the audience to ask questions (“that end with a question mark!”), and following a lively Q&A session, O’Hanlon left the audience with a clear opinion: “Ethically Ukraine is in the right, and Russia is in the wrong.” Everyone then flowed out of Rabb Hall and upstairs to the Newsfeed Café, where they were met with catered snacks and soft drinks, other participants to debrief with, and (after waiting in a line of excited attendees) the opportunity to talk to O’Hanlon himself.

Having attended the 2023 NATO Youth Summit the day before, I found this program pertinent and engaging. The event itself exemplified the importance of engaging a diverse audience and fostering informed conversations around complex challenges, and O’Hanlon’s lecture touched on the paradoxical ethos that war itself may be a crime, but might not be a war crime. This event was my first experience with WorldBoston, and the bar has been set quite high. I look forward to seeing what’s to come in the future.